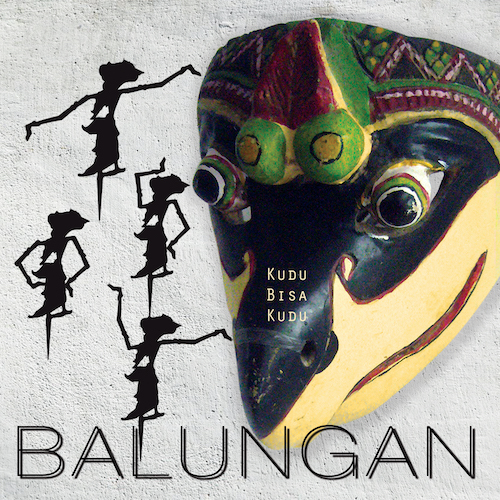

KUDU BISA KUDU RUNE 484 |

"May

well be the best project Chenevier has ever been involved in -- and

from Etron Fou on that covers a lot of magnificent ground. Loud,

immediate, and compelling." - a buyer of the album By the end of 2022, Indonesia will see the completion of its first high-speed rail line, an 88-mile-long section linking the nation’s longtime capital, Jakarta, to Java’s second largest city, Bandung. According to the globe-trotting musicians of Balungan, however, the train à grande vitesse is already at the station. The 13-member band kicks off its debut, Kudu Bisa Kudu, with the nostalgic steam whistle and intentionally garbled boarding call of “Javanese TGV”, but as soon as Franck Testut’s driving bassline gears ups, it’s clear that we’re riding a 21st-century conveyance. Gang vocals, hairpin-curve guitars, and accelerating arpeggios played on tuned percussion also announce that this is a multicultural journey—and in fact the group is made up of seven of Java’s most open-minded gamelan virtuosos, plus six equally adventurous rock musicians from the south of France. Gamelan—Indonesia’s national music, based on intricately subdivided polyrhythms and played on shining, lavishly decorated bronze metallophones—has been an influence on European and North American musicians for more than a century, arguably beginning with the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle in Paris. There, French composers including Maurice Ravel and Claude Debussy first heard a Javanese gamelan ensemble, and immediately reconsidered their notions of what music could be—and the repercussions, so to speak, are still being felt. Artists as diverse as jazz traveller Don Cherry, pioneering minimalist Lou Harrison, and the progressive rock groups Gong and King Crimson have incorporated gamelan-like rhythms into their sound, and while the influence of European music on Indonesia has been less widely celebrated, it’s there: think of the guitarist Dewa Budjana, whom sometimes works Balinese motifs into his blazing fusion jazz. But there’s never been a gamelan-based cultural exchange as equitable as Balungan, named after the Javanese word for “skeleton”, which is also used to describe the core melody of a musical composition. Nor has there been one as loud. The Javanese members of the band attack their gendèrs, gongs, and bonangs “like a rock ensemble,” says drummer and project sparkplug Guigou Chenevier, “and this was really great to see and to share with them.” The Balungan project began when Chenevier — a legend in progressive-rock circles for his work with Etron Fou Leloublan, Fred Frith, and others — initially answered a call for a gamelan workshop in Marseilles. The hook was the opportunity to work with a cadre of Javanese instructors, followed by a visit to their home in Yogyakarta, the musical capital of central Java. The Avignon resident recalls that when he learned “the workshop involved making music with these people eight hours a day for 15 days" and that travel costs were covered, he said “Wow, I want to do that!’” Following that first excursion, Chenevier invited his Javanese friends to his home town, and things grew from there. “They explained to me that they wanted to exchange their culture with something new, because they felt that if they didn’t do that Javanese music and gamelan music would just die,” the drummer notes. “So I said “Wow! Okay, let’s do something together.’ In total, we had three different times in Java and they came three different times in France, and that’s how it started.” Once the members of the band were in place, aesthetic parameters were quickly established. Balungan wasn’t going to be about rock musicians playing gamelan, or vice versa: one singular feature of the live concert immortalized on Kudu Bisa Kudu is that every musician has written a piece, with the arrangements developed collectively. Chenevier, for example, contributes “The Guy I Am”, which frames a text from the great Hindu epic, the Ramayana, in clanging metallophones, Beefheartesque slide guitars, and clattering drums that gradually build to an ecstatically psychedelic climax. Sapto Raharjo’s “Kangen”, in contrast, opens in an almost traditional manner, but soon veers towards something that recalls pop metal, with power-chord guitars, anthemic singing, and a surging rock chorus. What’s most impressive about Kudu Bisa Kudu, perhaps, is that the ensemble manages to be both coherent and diverse, even in the live setting. Despite its size and schizophonic nature, Balungan sounds like a band, in part because the performers, recognizing that their time together would be limited, honoured their commitment to rehearsing eight hours a day, every day. But Chenevier also points out that he and his fellow French musicians were inspired by their Javanese colleagues’ inclusive and boundary-free attitude towards art and life. “In Javanese culture one thing that’s very important is the spiritual aspect, but not in the sense of strict religion,” he says. “For example, lot of people in Central Java, they can be at the same time Muslim and Buddhist. It’s no problem for them. And of course this way of seeing the world is very important in the way they make music and art and all that. “When you are a musician playing gamelan in Java, you learn everything at first,” he continues. “You learn music, of course, but you also learn dance, you learn poetry, you learn puppets… all that goes into the full show of the shadow theatre. And only then do you choose a speciality. So it was very interesting working with these people, because they are very big fans of the stage, of theatre, and they know how to add often very funny stuff on-stage. So it was very alive; each performance we did was a surprise.” Chenevier is still contemplating how his work with his Javanese counterparts will change how he approaches music in future, although he notes that it certainly reinforces his desire to operate in a collaborative way—as he has already done on his solo albums Le Batteur Est Le Meilleur Ami Du Musicien, an early exercise in file-sharing with musicians from all over the world, and Les Rumeurs De La Ville, which includes performances from amateur musicians from Avignon as well as a number of virtuosi. But Balungan’s most important lesson, he offers, has to do with the “why” of making music. “On different occasions journalists would ask us why we were doing this project,” he says. “And generally the Javanese people, they were answering in a way that a French guy never would, which was that it was just about fraternité. That was very beautiful and very simple, and at least as important as the rest of the project: the human exchange, the way they welcomed us when we were there, and also the incredible places where we played some concerts in Java. They were just amazing. I never could have imagined such a thing before.” Will he imagine such a thing again? That remains to be seen, Chenevier admits. Between the COVID-19 pandemic, hardening racial attitudes in France, and the perils of the global economy, it seems unlikely that Balungan will have a second act—although his memories of this beautiful project and the circumstances that shaped it will remain. Even now, he says, he still dreams of all-day rehearsals in the heat and humidity of Central Java, the cooling rains that would come every night, and the hair-raising scooter rides home afterwards. “It’s a strong memory,” he says, “a very deep impression that will stay inside me forever.” And listeners may well feel the same once they hear this music.Kudu Bisa Kudu press release |

PRESS RELEASES

Kudu Bisa Kudu press release